Author: Rachel Viney, Historical Story Researcher at the Leach Pottery

Bernard Leach’s encounter with raku in Japan in 1911 changed his life and had a profound influence on the direction of pottery making in the UK.

About raku

Raku’s origins date back to sixteenth-century Japan and the art of the tea ceremony. Although many types of ceramics have been used in the tea ceremony, it is raku ware that is considered to possess all the qualities looked for in a perfect tea bowl.

The low firing temperature for raku, and the small amount of apparatus involved, mean that it is an accessible method of making pots. That, plus the poor heat-conducting qualities of raku vessels themselves (they can be held comfortably in the hands), helped make raku a favourite with Japanese tea-masters.

In the raku firing “the pot is covered in glaze, placed in a glowing hot kiln and left until the glaze has matured, then removed and allowed to cool rapidly – the whole process taking as little as an hour, rather than the more usual day or two.” (Freestone and Gaimster, 1997)

“Ticks and tings” – Bernard Leach’s first encounter with raku

That all-important first encounter with raku was described by Bernard Leach’s son David in an interview with Tim Andrews. It took place at a tea ceremony where, to Bernard Leach’s surprise, “part of the afternoon’s activity involved an itinerant raku potter. All the guests were invited to participate in the decoration of unglazed raku pots in the Japanese manner, mostly consisting of characters, forming perhaps a poem or a verse.” (Andrews, 1995)

Bernard Leach struggled with the unfamiliar paints and long brushes, but produced – according to his biographer, Emmanuel Cooper, a design he recalled from a Ming porcelain dish of a parrot balancing on one foot on a stand, with at one end a small seed container and at the other a water container (Cooper, 2003). This decorated pot was then dipped in a tip of white lead glaze and set around the top of the kiln to warm and dry for a few minutes before being placed with long-handled tongs in an inner chamber. In A Potter’s Book Leach recalls the moment when: “The covers were removed and the glowing pieces taken out one by one and placed on tiles, while the glow slowly faded and the true colours came out accompanied by curious sharp ticks and tings as the crackle began to form in the cooling, shrinking glaze”(Leach, 1940).

Leach was hooked, and started ‘baking pots’, as he described it, as a regular routine. A diary entry reveals that he sold 10 raku pots at an exhibition just two months later, in April 1911 (CAPBL, Vol II). Leach also resolved to find a master in the craft, and after visiting several potters and an abortive stint as a student with one of them, was introduced to Urano Shigekichi, who held the dynastic title of sixth Kenzan.

Leach was to spend two days a week for two years as Urano’s student, with his friend Tomimoto initially serving as interpreter. Although Urano did not throw (throwing was regarded as a profession in its own right), Leach was keen to acquire this skill too, and learned how to throw and trim pots on a Japanese wheel, which traditionally is pushed round with a stick and revolves clockwise.

Ultimately Kenzan conferred on Leach the honour of succeeding him as the seventh Kenzan. Although Leach later resigned the inheritance, he did use the title when speaking about the artist.

Raku in the early days of the Leach Pottery

David Leach recalled to Tim Andrews that when his father set up the Leach Pottery with Shoji Hamada, they had “a few raku firings there together from 1920-1923 … before Hamada went back to Japan in 1923”.

The making of raku continued after Hamada’s departure. David Leach recalled that in 1925 Bernard Leach decided that “raku might be the thing to draw visitors to the pottery for one afternoon a week”. David remembered helping on these occasions and making batches of pots: “little shallow dishes, ashtrays and bowls, little bottle vases.”

Murray Fieldhouse described these raku firings: “The practice was to have a slipware firing going so that by 2pm it had reached a temperature of 800C at the top. Biscuit pots in a refractory body were produced and displayed on shelves for visitors to paint with raku underglaze colours. The decorated pots were taken out to Bernard Leach who dipped them in a raku glaze: white lead 66, quartz 30, China clay 4. After drying, the pots were placed in the kiln by removing two bricks in the crown. During the firing the visitors had tea and the colourful pieces would be ready for them to take away.” (Fieldhouse, 1960) David Leach recalled that the “tea was quite substantial, considering it was only a shilling, and included saffron buns from Mrs Penburthy down at the Stennack, rock buns baked the previous morning, splits and cream”.

Raku firings at the Leach Pottery ceased around the mid 1930s. However, the 1961 Leach retrospective, ‘Bernard Leach: 50 Years a Potter’, held at the Arts Council in London before going on tour to Bradford and Newcastle, included some of Leach’s first raku pots.

Raku comes full circle at the Leach Pottery

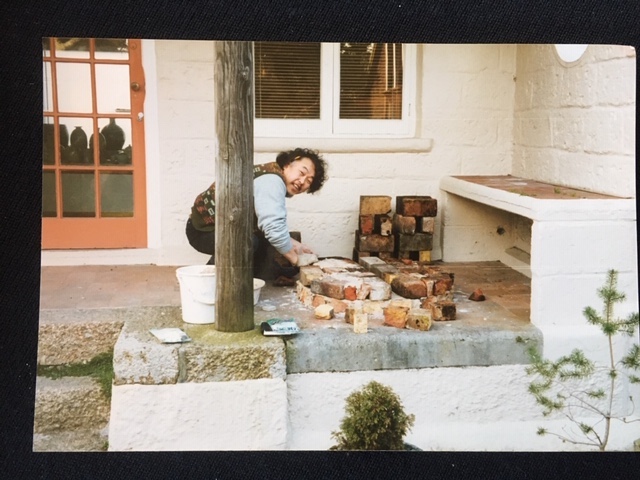

Raku firing took place one further time at the Leach Pottery, with the construction in 2002 of a small kiln similar to the one Bernard Leach first encountered in Japan. Fittingly, it was built by two generations of a Japanese potting dynasty – Yasuo Terada, his son Teppei and daughter Orie – together with former Leach assistant Jason Wason. Jason’s wife, Joanna Wason, recalls that while Yasuo was staying at their house he was transfixed by their coal fire – and this was the material used to fire the new kiln in March 2002. Among the guests that day was David Leach, who had participated in those early Leach Pottery raku events almost 80 years before. The kiln body stands today on what is now the wooden walkway behind the Pottery shop, while the lid of the kiln, which is in three parts, can be seen in the museum.

About the Author

Rachel Viney is a cultural researcher, writer and editor, specialising in the visual arts, publishing and broadcasting. Having loved studio pots for as long as she can remember, she’s thrilled to be working with the Leach Pottery in its centenary year.

Sources

Andrews, Tim, 2005. Raku. 2nd ed. London: A&C Black, 2005.

Fieldhouse, M, 1960. Workshop Visit – The Leach Pottery. In T. Barrow, ed., 1960. Bernard Leach: Essays in Appreciation. Wellington, The New Zealand Potter. https://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/media/uploads/2018_08/NZPotter_v5_n1.pdf

Cooper, Emmanuel, 2003. Bernard Leach: Life & Work. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Crafts Study Centre Bath, 1987. Catalogue of the Additional Papers of Bernard Leach, Volume II (ref. 10875). https://www.csc.uca.ac.uk/s/Bernard-Leach-Archive-Volume-II.pdf

Freestone, I. and Gaimster, D. eds., 1997. Pottery in the Making: World Ceramic Traditions. London: British Museum Press.

Leach, Bernard, 1940. A Potter’s Book. London: Faber & Faber.